Your cart is currently empty!

As Dr. Padilla, a physical therapist and clinic owner here in Wasco, CA, I’ve had the opportunity to help many people in our community recover from a variety of injuries and get back to doing what they love. My own journey, detailed in the Wasco Tribune, has given me a unique perspective on the importance of personalized care and the resilience of the human body. One of the most common and challenging injuries I see is the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tear. I’m also inspired by stories like the one from the Community Medical Center about burn survivors; it reminds me that recovery is possible even from the most severe injuries. ACL injuries, while different, also require a focused and dedicated approach.

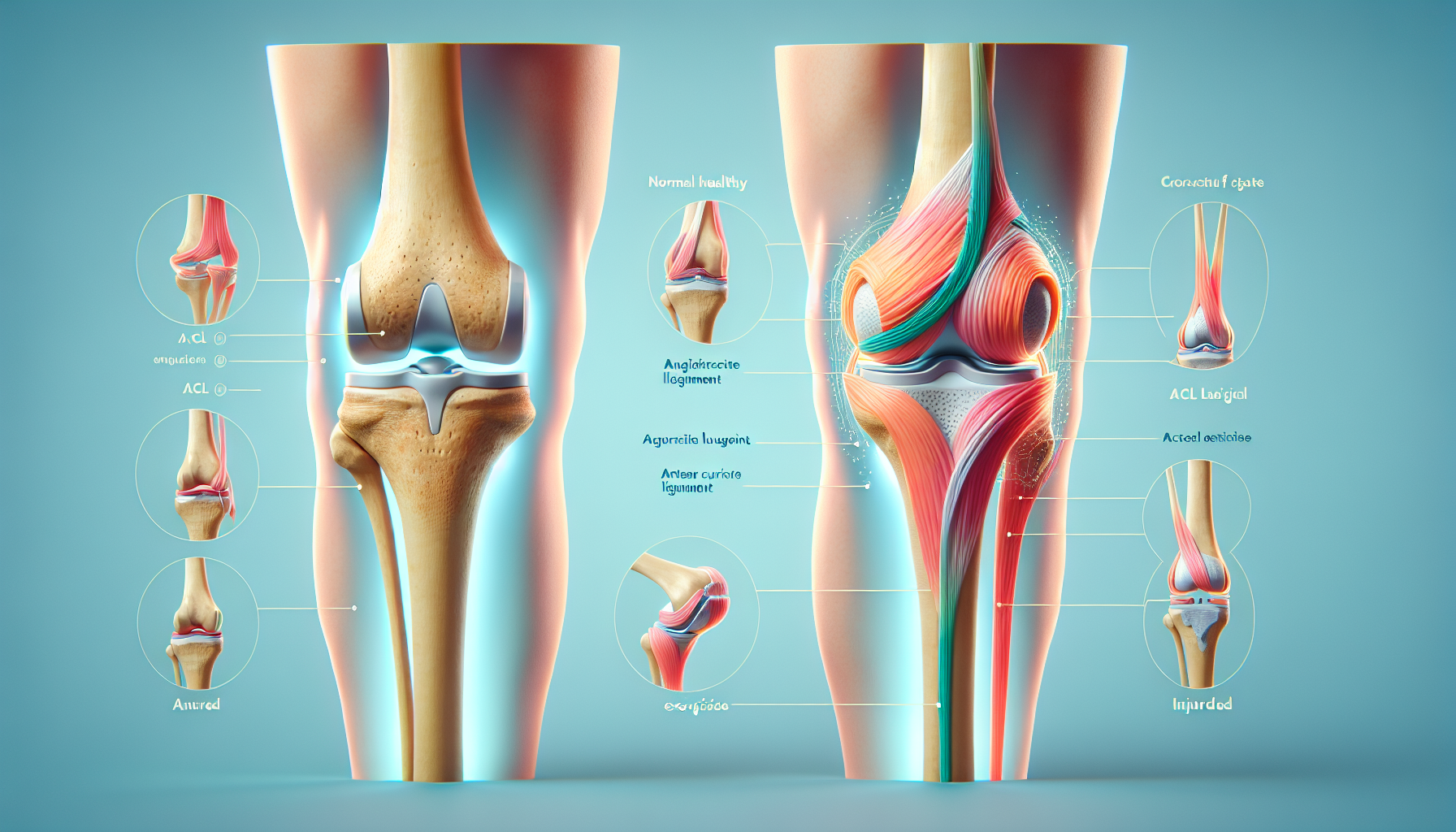

Understanding ACL Injuries

The knee joint relies on a complex interplay of bones, cartilage, tendons, and ligaments for stability and movement. The ACL is one of the four primary ligaments in the knee, connecting the thighbone (femur) to the shinbone (tibia). Its primary functions are crucial: preventing the tibia from sliding too far forward relative to the femur and providing rotational stability to the knee joint. It acts much like a strong rope, essential for controlling knee movement during various activities.

ACL injuries are unfortunately quite common, especially in athletes. These injuries often occur during high-demand sports that involve:

- Sudden stops

- Jumping

- Rapid changes in direction

Think of sports like soccer, basketball, football, volleyball, and skiing. However, it’s important to remember that ACL tears can happen to anyone, even from an awkward step or pivot.

What Causes an ACL Tear?

ACL tears usually happen when the ligament is stressed beyond its capacity. This can occur due to:

- Sudden Deceleration and Change of Direction (Cutting): Quickly slowing down and changing direction puts significant rotational and translational forces on the knee.

- Pivoting: Twisting the body while the foot remains firmly planted on the ground stresses the ACL.

- Awkward Landings: Landing from a jump, especially on a straightened knee or in an off-balance position, can overload the ligament.

- Sudden Stops: Abruptly stopping while running generates considerable force through the knee joint.

- Direct contact: Such as a blow to the side of the knee.

These are often non-contact injuries, meaning they happen due to movement, not necessarily a direct blow. Factors like poor muscle control, weakness (especially in the hamstrings), and improper movement patterns (like letting the knee collapse inward, known as valgus collapse) can increase the risk. As a physical therapist, I often work with patients to correct these movement patterns, which is crucial for both recovery and injury prevention.

Risk factors for ACL injuries include:

- Participation in high-risk sports

- Being female (studies have shown a higher incidence in female athletes)

- Poor conditioning

- Faulty movement patterns

- Improper equipment

- Playing surface (some studies suggest a higher risk on artificial turf)

Symptoms of an ACL Injury

If you’ve torn your ACL, you might experience:

- An audible “pop” in the knee

- Severe pain

- Rapid swelling

- Loss of range of motion

- A feeling of instability or that the knee is “giving way”

- Tenderness

- Difficulty walking

It’s important to get prompt medical attention if you suspect an ACL injury. Ignoring it can lead to further damage within the knee, such as to the menisci (cartilage pads).

Diagnosis and Associated Injuries

Diagnosing an ACL tear involves a physical exam, where an experienced physical therapist can often detect the injury, and imaging tests. We check for swelling, tenderness, and range of motion, and perform specific tests to assess the ACL’s integrity.

Imaging tests may include:

- X-rays: To rule out fractures.

- MRI: The gold standard for visualizing soft tissues like ligaments, showing the extent of the tear and any other damage.

- Ultrasound: Can visualize ligaments, tendons, and muscles.

ACL tears rarely happen alone. Other knee structures, like the meniscus, cartilage, and other ligaments, are often also injured. These associated injuries can make treatment more complex.

Ligament injuries are graded by severity:

- Grade 1: The ligament is stretched but not torn.

- Grade 2: The ligament is stretched and partially torn.

- Grade 3: The ligament is completely torn.

Grade 3 tears often require surgery, especially for those wanting to return to high-level activities.

Surgical Options: Reconstruction vs. Repair

If the ACL is completely torn, it usually won’t heal on its own. Surgery is often recommended for active individuals. The two main surgical options are:

- ACL Reconstruction (ACLR): This is the most common procedure. The damaged ACL is removed and replaced with a graft (tissue taken from another part of your body or from a donor). Grafts can be:

- Autograft: From your own body (patellar tendon, hamstring, quadriceps tendon).

- Allograft: From a deceased donor.

ACLR is typically done arthroscopically (minimally invasively) and has generally good outcomes for restoring knee stability and allowing return to high activity levels. - ACL Repair: This involves reattaching the torn ACL. It’s less common and typically only suitable for specific types of tears (usually where the ligament tears off the femur) with good tissue quality. Repair techniques may involve sutures and/or augmentation with internal bracing or biological scaffolds. While less invasive, ACL repair currently has a higher risk of failure and re-operation compared to reconstruction.

The choice of surgery influences the rehabilitation process. Reconstruction is more reliable for long-term stability, which is crucial for athletes and active individuals.

The Importance of Physical Therapy

Whether you have surgery or not, physical therapy is essential for ACL recovery. It’s not just about exercise; it’s a structured program to safely guide you back to your desired activity level while minimizing the risk of re-injury. As a physical therapist, I play a vital role in this process.

Physical therapy helps to:

- Restore range of motion

- Rebuild muscle strength (quadriceps, hamstrings, glutes)

- Improve balance and proprioception (joint position sense)

- Address factors that contributed to the injury, like muscle imbalances and poor movement patterns

- Manage pain and swelling

- Ensure safe progression of activities

- Retrain muscle firing patterns and improve coordination

- Provide patient education on the healing process and prevention strategies

A comprehensive ACL rehabilitation program includes:

- Assessment: Conducting a thorough initial evaluation and ongoing assessments of pain, swelling, range of motion, muscle strength, gait mechanics, balance, and functional movement patterns.

- Individualized Plan: Developing a personalized, criterion-based rehabilitation plan tailored to the specific surgical procedure, the patient’s goals, and their progress.

- Manual Therapy: Employing hands-on techniques such as joint mobilizations, soft tissue massage, and stretching to reduce pain, decrease swelling, improve tissue flexibility, and restore normal joint mechanics.

- Therapeutic Exercise: Selecting and supervising specific exercises targeting:

- Range of Motion

- Strength (open-chain and closed-chain exercises)

- Balance and Proprioception

- Neuromuscular Re-education

- Gait Training: Analyzing and correcting walking patterns.

- Functional and Sport-Specific Training: Progressing to activities that mimic your daily life or sport, including running, jumping, cutting, and pivoting.

- Return-to-Sport (RTS) Testing: Administering a battery of objective tests to determine readiness to return to activity.

- Patient Education: Providing crucial information about the healing process, activity modifications, precautions, home exercise programs, and long-term injury prevention.

Phases of ACL Rehabilitation (Post-Surgery)

ACL rehabilitation is divided into phases, with progression based on meeting specific criteria, not just time. Prehabilitation (therapy before surgery) can improve post-operative outcomes. Here’s a more detailed look at each phase:

- Phase 1: Protection and Early Motion (Weeks 0-4): Focuses on protecting the graft, controlling pain and swelling, restoring full knee extension, and initiating gentle movement.

- Goals: Protect the surgical repair, minimize pain and swelling, restore full passive knee extension, gradually increase knee flexion, restore patellar mobility, re-establish quadriceps control, begin weight-bearing as tolerated.

- Example Exercises: Range of motion exercises (heel slides, wall slides), activation exercises (quadriceps sets, straight leg raises), gentle weight shifts.

- Precautions: Follow weight-bearing instructions, avoid placing pillows under the knee, avoid loaded knee extension, protect the graft from twisting. For hamstring grafts, avoid active hamstring contractions. For meniscus repairs, limit weight-bearing flexion.

- Criteria for Progression: Full passive knee extension, knee flexion of approximately 90-110 degrees, ability to perform a straight leg raise without lag, reduced swelling, good quadriceps control, ability to walk with a normalized gait.

- Phase 2: Building Strength and Control (Weeks 4-12): Focuses on progressively building strength, restoring full range of motion, and improving balance.

- Goals: Achieve full knee ROM, increase strength in major muscle groups, enhance balance and proprioception, normalize gait, introduce low-impact cardio.

- Example Exercises: Closed kinetic chain strength exercises (squats, lunges, leg press), open kinetic chain strength exercises (hamstring curls, knee extensions – with caution), balance exercises (single leg stance), cardio (stationary cycling, elliptical).

- Precautions: Avoid activities that cause pain or swelling, monitor for anterior knee pain, ensure proper form, respect graft healing. No isolated resisted hamstring work until 8-12 weeks for hamstring grafts.

- Criteria for Progression: Full, pain-free ROM, minimal to no swelling, adequate strength gains, good single-leg balance, normalized walking gait.

- Phase 3: Developing Power and Sport-Specific Skills (Months 3-6): Introduces more dynamic activities, focusing on power, agility, and sport-specific movements.

- Goals: Develop muscular power and endurance, introduce plyometrics (jumping and landing), initiate agility drills, begin running, introduce sport-specific movements.

- Example Exercises: Advanced strength exercises, plyometrics (bilateral and single-leg jumps), agility drills (cone weaves, cutting drills), running program, sport-specific drills.

- Precautions: Meet criteria before starting running/plyometrics, gradual progression, monitor for pain/swelling, emphasize movement quality.

- Criteria for Progression: Successful completion of running progression, good mechanics with plyometrics/agility, continued strength improvement.

- Phase 4: Return to Sport Readiness (Months 6-12+): Focuses on preparing for the demands of your sport and ensuring you meet objective return-to-sport criteria.

- Goals: Achieve objective RTS criteria, develop sport-specific conditioning, master complex sport movements, address psychological readiness, facilitate gradual return to practice/play, establish a maintenance program.

- Example Exercises: Advanced agility and sport-specific drills, advanced plyometrics, conditioning, practice/game integration, maintenance program (strength, plyometrics, balance).

- Precautions: Do not return based on time alone, must pass objective tests, gradual return, monitor symptoms, address psychological factors.

- Criteria for Progression: Meeting all RTS criteria.

Here’s a table summarizing the structured path to recovery:

ACL Rehabilitation: A Structured Path to Recovery

| Phase | Timeframe (Approx.) | Key Goals | Exercises | Precautions | Progression Criteria |

| 1: Protection & Early Motion | 0-4 Weeks | Protect graft, ↓ pain/swelling, restore full extension, initiate early motion | Heel slides, quad sets, straight leg raises, patellar mobilizations | WB restrictions, avoid pillow under knee, no loaded OKC extension | Full extension, 90-110° flexion, SLR without lag, minimal swelling, normalized gait |

| 2: Strength & Control | 4-12 Weeks | Full ROM, ↑ strength, improve balance & proprioception | Squats, lunges, leg press, hamstring curls (cautious), single-leg stance | Avoid pain/swelling, monitor anterior knee pain, proper form, respect graft healing | Full ROM, minimal swelling, adequate strength, good single-leg balance, normalized gait |

| 3: Power & Sport-Specific | 3-6 Months | Develop power & endurance, introduce plyometrics & agility | Advanced strength, bilateral/single-leg jumps, cutting drills, running program | Meet criteria for impact, gradual progression, monitor pain/swelling, emphasize movement quality | Successful running progression, good plyometrics/agility mechanics, continued strength gains |

| 4: Return to Sport Readiness | 6-12+ Months | Achieve RTS criteria, sport-specific conditioning | High-intensity agility, advanced plyometrics, sport-specific drills, practice integration | Do NOT return based on time alone, must pass RTS tests, gradual return, address psychological factors | Meets all RTS criteria (strength symmetry, hop test symmetry, functional movement quality, psychological readiness) |

This table provides a clearer roadmap for understanding the ACL rehabilitation process.

Leave a Reply